Harley Earl: The Father of Automotive Design

Harley Earl, GM’s head of styling revolutionized car design, and in the process, produced some of the most influential and iconic cars of his era.

Rethinking Automotive Design

Given its centrality today, it’s easy to imagine that automotive aesthetics was always of primary concern to carmakers. But turning back to the early days of the automobile and we find a lot of boxy, utilitarian cars, the Ford Model T for example, that have almost as much in common with carriages and bicycles as they do modern cars. It took the work of designer Harley Earl for the American car to transform from a boring appliance to the mechanical personification of its owner’s dreams and aspirations.

From Coach Building to Concept Cars

Harley Early got his start in automotive design in his father’s workshop. J.W. Earl had founded Earl Carriage Works in California in 1889 and transitioned to automotive coachbuilding in 1908 (renaming the business Earl Automotive Works). There, Harley worked while attending Stanford University. Such was his devotion to design that he dropped out of college to help his father, who’s business now received contracts from film stars like “Fatty” Arbuckle.

It’s important to remember that most automotive manufacturers in the early 20th century didn’t do their own body work but instead left that to professional coachbuilders like the Earls. Harley wasn’t the most talented designer when it came to pencil sketches, instead he preferred to work with scale clay models. Though it’s standard design practice today, the use of clay modeling, which lent itself to the curvaceous designs Earl would become famous for, was a major innovation in the 1920s.

When J.W. Earl sold the business to one Don Lee, the new owner kept Harley on as the director of the workshop. It was there that GM’s Lawrence P. Fisher had stopped as part of his tour of the Cadillac dealers where he was introduced to the young Earl. Fisher commissioned Earl to design the new LaSalle for Cadillac’s new sister brand. So impressed with Earl’s design, GM’s head Alfred P. Sloan hired Earl to head a new “Art and Colour Section” for the company, the first dedicated design department at a major automaker.

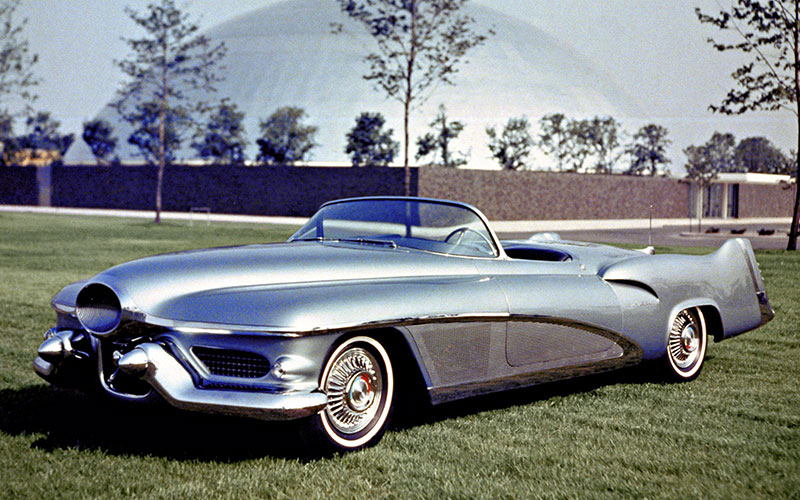

Buick Y-Job

Earl would go on to pioneer some of the most important design practices of the time and author many of the era’s signature designs. But one of his most notable contributions was the idea of the concept car and it’s first incarnation, the Buick Y-Job. In 1938, the notion of building a one-of car to illustrate and promote the future direction of a car company was unheard of. But just like today’s radical concept cars, the Buick Y-Job ignited the public’s imagination.

The Buick Y-Job was indeed a futuristic looking car in 1938. Long, low, and wide, the Y-Job’s body design featured huge bulging fenders, an integrated grille, wrap-around bumpers, a raked windshield, flush door handles, and lots of chrome, including chrome stripping racing across the body. The car had an expansive rear deck and very low profile for its day at complete with small 13-inch wheels. Thanks to the car’s aeronautic influence, it was given a “Y” moniker, like airplane prototypes.

They Y-Job’s sleek yet substantial look would go on to influenced automotive designs for the next two decades, including many of GM’s own.

’48 Cadillac

A decade later, under Earl’s direction, Frank Hersey designed the first automotive tailfin, supposedly inspired by the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, for the 1948 Cadillac Series 62. The tailfin would become all the rage in car design in the 1950s, sparking a sort of tailfin arms race between Earl and his equivalent, Virgil Exner, of Chrysler. The pinnacle product of this competition came in the form of the 1959 Cadillac Eldorado’s twin-bullet tailfins. (Read more on the Eldorado here.)

GM LeSabre

Aeronautic influence was a consistent through-line in Harley Earl’s work. And nowhere is that more apparent than in the 1951 GM LeSabre concept which featured a conical nose resembling a jet fighter plane. One of the LeSabre’s more interesting elements was its supercharged V8 that ran on a mixture of regular gasoline and methanol. In each of the car’s two prominent tail fins was a 20-gallon fuel tank, one for the gas and the other for the methanol, which was used under hard throttle application.

C1 Corvette

The Corvette remains singular among American cars. A two-seat sports car wholly dedicated to the thrills and chills of performance driving. For this we have Harley Earl to thank. In the early 1950s, Earl looked over at the sports cars coming out of England and Germany and felt a US carmaker could do well with one of their own.

Dubbed “Project Opel,” the Corvette’s original design featured a fiberglass body, then a new innovation, for cost and weight savings. Like Earl’s other designs, the EX-122 prototype featured smooth flowing lines that ensured, if nothing else, the car looked fast.

Debuting at the New York Auto Show in 1953, the Corvette prototype was a hit with the public and press alike. Despite looking fast, for the first two years the Corvette lacked a proper V8. Luckily, GM engineer Zora Arkus-Duntov lobbied successfully for the Vette to get an engine to match Earl’s speedy design. For more on the C1 Corvette, click here.

Design Denouement

Harley Earl retired from GM in 1958 at the age of 65 (then the forced retirement age at the company). In his thirty years of design, Earl was a consistent innovator. Along with GM head Alfred P. Sloan, Earl had helped pioneer the idea of “Designed Obsolescence” wherein a car would receive a new body redesign each year, encouraging car buyers to focus on fashion as much as practicality in their purchases. Earl positioned design as central to both a carmaker’s business plans and a car buyer’s choice of vehicle.

And while that might be his most lasting legacy, Harley Earl will probably remain most identified with his automotive designs of the 1950s, with their voluptuous swooping lines, copious use of chrome, and flamboyant tailfins.